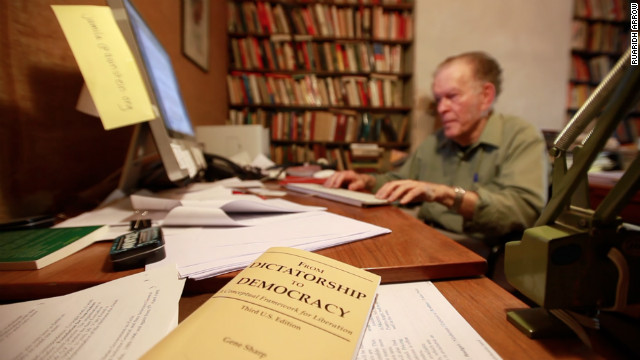

By Ruaridh Arrow

The Albert Einstein Institution has announced that Dr Gene Sharp passed away peacefully on the 28th January at his home in East Boston. He had recently celebrated his 90th Birthday.

For almost seven decades Gene dedicated his life to researching and writing on nonviolent means of struggle that might replace violence and war, his central thesis, that political power is held, not by rulers themselves, but by the willing consent of the people and institutions that support them. By studying techniques to undermine these institutions and pull them over to the democratic side, the ruler could be left powerless.

Born on the 21st January 1928 to the Reverend Paul Sharp, a traveling minister and Eva Sharp a school teacher, Gene studied first at Ohio State University where he received his undergraduate and masters degrees in political studies, before moving to New York where he wrote his first book on Gandhi’s use of nonviolent action. In 1953 he took a civil resistance position against conscription for the Korean War and was sentenced to two years incarceration at Danbury Connecticut. Just before his trial he wrote a compelling letter to Albert Einstein at Princeton telling him about his position on fighting in Korea and asking if he might write a foreword to his book on Gandhi. Einstein replied immediately offering to provide the foreword and giving permission for his letters to be quoted at the trial.

He wrote, “I earnestly admire you for your moral strength and can only hope although I really do not know that I would have acted as you did had I found myself in the same situation.” Einstein even found time to write letters of comfort to Gene’s mother after the sentence had been passed.

After his release, Gene worked with A.J Muste America’s most famous pacifist before travelling to London where he became Assistant Editor of Peace News and planned the first Aldermaston march against nuclear weapons in 1958. His leaflets urging the maintenance of nonviolent discipline during the march were the first materials on which Gerald Holtom’s iconic peace symbol were printed. He went on to study at the Institute of Ideas in Oslo under Professor Arna Naess and at Oxford University where he received his Dphil for a thesis which would become his most highly regarded work ‘The Politics of Nonviolent Action’.

After studying the teacher’s strike against the Quisling’s regime in Norway during the Second World War he pioneered the study of strategic nonviolent struggle as a deterrent to a Soviet invasion, arguing that a population well trained in nonviolent resistance could make themselves so unruleable that they might deter an occupying force and replace the need for nuclear weapons. His work was put to use in the successful civilian defense of the Baltic countries from Soviet forces in 1991 and again during the Moscow coup against Gorbachev later that year. The Lithuanian defense minister Audrius Butkevicius remarked later, ‘I would rather have this book than the nuclear bomb’.

He was also known for his 198 nonviolent methods, a product of his study of hundreds of years of nonviolent cases in history which he noted down over decades on small pieces of card tied up with rubber bands. The methods, finally compiled into a single document during his time studying at Oxford University, gave inspiration that the means of nonviolent action extended far beyond just street protests and marches.

During the first Intifada compilations of Gene’s work on civilian based defense were distributed among Palestinians by resistance leaders including Mubarak Awad and Sari Nuseibeh. The widespread use of the work lead to a meeting between Gene and Yasser Arafat in Tunisia where Gene implored Arafat to give up the violent component of the struggle against Israel and mark a new phase by calling for a nationwide hunger strike.

Gene was also present in Tiananmen Square in 1989 as the PLA tanks rolled in to crush the Chinese students uprising. For days he interviewed student leaders before the crackdown and smuggled the cassette recordings out past Chinese security by disguising them as Pink Floyd albums.

Three years later, after the imprisonment of Aung San Suu Kyi, Gene was smuggled into Burma to conduct training camps in nonviolent resistance for democrats and Burmese ethnic minorities in their jungle fortress of Manerplaw. Trainees were sent back into the cities in order to guide a potential revolution against the junta. The project came to little, but in preparing the Burmese for a nonviolent campaign he produced what would become possibly the most successful guide to nonviolent resistance ever written. ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ was designed as a generic guide to resistance for the Burmese, but its simple language and small size meant it was quickly translated by other democracy groups living in countries labouring under similar oppression.

‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ spread into more that 34 languages, used by people fighting tyranny everywhere from the jungles of Burma, to the streets of Serbia and the Arab Spring. In some cases the availability of his work was pivotal in the decision by opposition movements to commit to nonviolent methods rather than campaigns of violence.

The Serbian group OTPOR credited Gene’s work in their campaign to oust President Slobodan Milosevic as did many of the leaders of the ‘colour revolutions’ which followed in the Soviet successor states, including Georgia in 2003 and the Ukrainian Orange Revolution in 2004. Leaders from these struggles spread his work further afield, former OTPOR activists training the leaders of the Egyptian youth movement April 6 and members of similar organisations in Syria. The work continues to be used in Hong Kong, Venezuela and Burma among many others.

Gene was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on at least three occasions and won a number of international prizes including the Right Livelihood Award.

In 2012 a biographic documentary about his work, ‘How to Start a Revolution’ won a BAFTA award and was shown internationally and used screened in Occupy camps all over the world.

A statement from the Albert Einstein Institution read,

“Gene Sharp refused to retire and worked up until his death. A rare collection of orchids on the top floor of his home were his joy and respite. He enjoyed keeping animals, especially his dogs and exploring the wild spaces of Norway and Canada. He never married or had children, but he loved and was loved. He leaves behind generations of students of his work all over the world who are better able to win political freedom and resist oppression than ever before. He has set down his pen for the last time, but his work will continue forever.”

You can watch How to Start a Revolution, the film about his life here http://vimeo.com/ondemand/4878 . For commemorative public screening please contact [email protected]

The institution is asking friends and those that found his work useful not to send flowers, but instead donate to furthering the work of his institution on the donate link here. www.aeinstein.org