By The Economist

The ruling party will probably win the coming election, but corruption is weakening it

IT IS fitting that the black-and-red flag of Angola is hardly distinguishable from that of its ruling party. The People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) has led the country since independence from Portugal in 1975. At the parliamentary election in 2008 it won 82% of the vote; in 2012 it won 72%. Few doubt it will win again when Angolans go to the polls on August 23rd.

Many Angolans credit the MPLA with bringing peace to the country after nearly three decades of civil war that ended in 2002. The party then presided over an oil-fuelled boom, with annual GDP growth averaging 7.2% between 2003 and 2015. New roads, railways and other infrastructure won it the support of voters. But just in case, the party is also accused of beating opponents, bribing local chiefs and keeping a tight grip on the media.

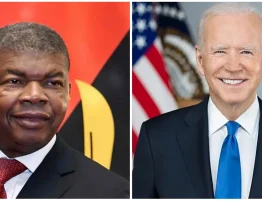

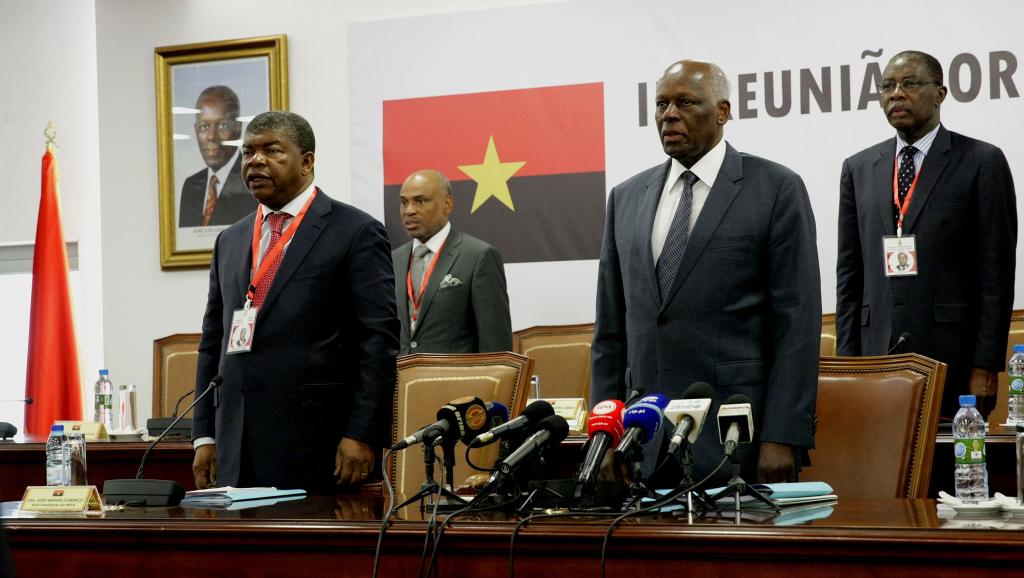

There are signs, though, that the MPLA’s stranglehold on Angolan politics is loosening. Its leader, José Eduardo dos Santos, is stepping down as president after 38 years in power. His handpicked successor, João Lourenço, does not have the same standing within the party—nor does he inspire the same fear in its opponents. Moreover, 66% of the country’s 28m people are under 25. Many will be voting for the first time. With little memory of the war, they tend to be more cynical about the MPLA.

The party’s lustre has faded as the low price of oil turned Angola’s boom into a bust. In April the official statistics agency reported that GDP shrank by nearly 4% last year (it has since removed the figure from its website). The unemployment rate hovers above 20%. Foreign firms are leaving the country because of a shortage of hard currency. On the streets of Luanda, the capital, a dollar changes hands for more than double the official rate. Many Angolans wonder why the country’s oil wealth has not made them better off.

A big part of the answer is corruption. According to reports, the government is unable to account for billions of dollars in public funds over the past decade. In 2012 the IMF documented shoddy book-keeping at Sonangol, the national oil company. Anti-corruption investigators in China have probed its deals with Angola—and made arrests. Big oil-for-infrastructure contracts, often involving Mr dos Santos’s inner circle, seem to be deliberately opaque. The country ranks 164th of 176 on the Corruption Perceptions Index compiled by Transparency International, a watchdog.

Still, few Angolans seem to be giving up on the MPLA. Polling data are fuzzy, but a survey conducted in July, before serious campaigning began, found that 61% of them plan to vote for the party. It is expected to lose support in Angola’s cities and may even lose most of the seats in Luanda, where the party was founded. The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), the MPLA’s civil-war adversary and the main opposition party, and CASA-CE, a coalition of parties formed in 2012 by a former UNITA leader, stand to benefit. CASA-CE’s push for political and economic reforms is resonating with young urban voters.

The largest party in parliament selects the president, so Mr Lourenço, a former defence minister, will certainly get the job. He enjoys strong ties to the army, but some question whether he has the clout to clean up the government and implement much-needed reforms. He was not the first choice of Mr dos Santos, who is said to have wanted a successor from his own inner circle. Opposition from within the party forced him to back away from that plan. But he is not completely giving way to Mr Lourenço. Though he is stepping down from the presidency, he will continue to lead the MPLA. His eldest son will still run Angola’s sovereign-wealth fund, while his daughter heads Sonangol.

“The MPLA needs to free itself of the control of dos Santos,” says Marcolino Moco, who served as Mr dos Santos’s prime minister and is now a critic of the government. But without a strong mandate, Mr Lourenço may find it difficult to do what is necessary. The government must devalue the currency, say analysts. Fast-rising debt, which helped the government maintain spending in the run-up to the election, may force Angola to ask the IMF for help. For any benefits to trickle down to the masses, Mr Lourenço must tackle corruption. To do that, he must stand up to the elite in his own party.