Angolans go to the polls on Wednesday to pick their first new president in decades, but money-laundering and bribery cases in Portugal are raising questions about the ability of Africa’s No. 2 oil producer to tackle corruption and right its economy.

By

Gabriele Steinhauser in Luanda, Angola, and

Patricia Kowsmann in Lisbon

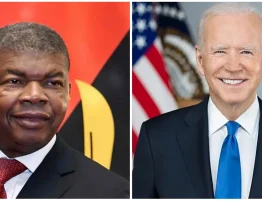

João Lourenço, the front-running presidential candidate of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, attends a campaign rally in Lobito, Angola, on Aug. 17.Photo: MANUEL DE ALMEIDA/European Pressphoto Agency

Angolans go to the polls this week to pick their first new president in decades, but money-laundering and bribery cases are raising questions about the ability of Africa’s No. 2 oil producer to tackle corruption and right its economy.

João Lourenço, a former general who is favored to win Wednesday’s election, has promised to increase transparency as low oil prices have crippled government resources and the kwanza currency.

How he responds to the cases in the country’s old colonial master Portugal will go a long way toward determining whether Angola, which Transparency International has rated one of the world’s most corrupt nations, can clean up its act.

Although Angola’s per-capita gross domestic product of $4,342 is among the highest in sub-Saharan Africa, the majority of its 29 million people live in poverty. At 52.4 years, it has the world’s second-lowest average life expectancy, behind only much poorer Sierra Leone.

The cases have implicated key members of the regime of longtime President José Eduardo dos Santos, and Sonangol, the state oil company that has powered the southern African nation’s economy since the country emerged from civil war in 2002.

They shine a light on how prominent Angolans were allegedly able to funnel millions of dollars into luxury Portuguese properties even as its citizens remained among the world’s poorest, but also illustrate European authorities’ heightened efforts to rein in potentially illicit financial flows from Africa.

A spokesman for Mr. dos Santos, who isn’t implicated in any of the cases, declined to comment.

“The Portuguese seem to be kicking into action,” said Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, associate professor of African politics at Oxford University.