Why Angola meddles so much in its giant northern neighbour

By The Economist

IN THE nightclubs of Kinshasa, the raucous capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, adverts are everywhere for Congolese beer. From Primus, one of the biggest brands, with its label in the colours of the national flag, to Mützig, a German-themed lager, there is a choice that would be enviable in other African countries. The brews are typically served in intimidating 750ml bottles. Yet these days, ask for a beer and you are as likely to be given a can of Cuca, a less appealing Angolan fizz. It is not just beer: walk through a Kinois supermarket and every other product seems to be from Angola.

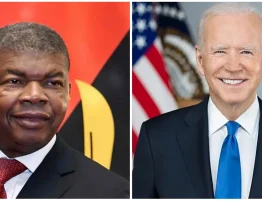

For over a year Angolan goods have flooded into Congo—so much so that on August 28th the government announced that it would try to ban the imports. Congolese businessmen complain that they cannot compete with Angolan traders, because their aim is not to make a profit, but to acquire dollars (access to which is restricted in Angola). Yet it is not just Angolan economic policy that affects Congo; so too do its politics. Of the country’s nine neighbours, none matters more. The presidency of Joseph Kabila, in power since 2001, depends in part on Angolan support. But as Angola inaugurates a new president, to replace José Eduardo Dos Santos, its egregious dictator for the past 38 years, relations between the two countries may be tested.

Angola and Congo are intimately linked by geography. First, there is oil—the mainstay of Angola’s economy. Cabinda, the exclave where much of Angola’s oil is produced, is separated from the mainland by a strip of Congo. Much of Angola’s offshore oil production happens in Congolese waters. Second is the 2,600km border between the two countries. During the long civil war in Angola, enemies of the MPLA, its ruling party, found in Congo a useful hiding place. That has put the country “at the top of Angola’s foreign-policy priorities” for the past 20 years, says Stephanie Wolters of the Institute for Security Studies, a think-tank in South Africa.

Of the many countries that have meddled in Congo since the end of the cold war, Angola has arguably wielded the strongest influence. During the second Congo war in 1998, when Rwanda and Uganda attempted to depose Laurent Kabila, Joseph’s father and president at the time, it was Angolan (and Zimbabwean) troops who stopped the advance. In 2001, as the war raged on, Laurent Kabila was assassinated. Angola was one of several suspects, and helped engineer the succession of his son.

Angola has backed Mr Kabila, but its support is limited. When he refused to give up power at the end of his second term last year, as mandated by the constitution, Angola pressed him to negotiate with the opposition. He did, leading to a power-sharing deal that allows him to stay in office for one more year while elections are organised. But that deal is in tatters. The opposition has split and Mr Kabila still claims that insecurity makes holding elections impossible. In the past year, a dispute over the succession of a traditional chief in Kasai, a region on the Angolan border, has turned into a bloody insurgency against the government. Over 1m people have been displaced, tens of thousands of whom have flooded into Angola. A series of prison breaks, including one involving 4,000 detainees in Kinshasa, has put even peaceful parts of the country on edge.

The Southern African Development Community, of which Congo and Angola are members, has accepted Mr Kabila’s delays in organising elections. But that will not last. On August 19th Sindika Dokolo, an art-collecting Congolese businessman who is the son-in-law of Mr Dos Santos, and other Congolese activists published a “manifesto” telling Mr Kabila to step down and calling for civil disobedience if he does not by the end of the year. Mr Dokolo, who surely has the backing of his father-in-law, has also met Moïse Katumbi, another wealthy Congolese exile, who aspires to replace Mr Kabila. Mr Dokolo’s activism has clearly unnerved the Congolese. In July, a court sentenced him in absentia to a year in prison for real-estate fraud.

Mr Dos Santos, who retains vast influence in Angola, fears chaos in Congo. He also wants to be on the right side of whoever succeeds Mr Kabila. (He has painful memories of a predecessor, Mobutu Sese Seko, who was openly hostile.) Mr Kabila is clinging tightly to his throne, but if he starts to lose control, his southern neighbours may well give him an extra shove.

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa section of the print edition under the headline “A tale of two kleptocracies”