Bloomberg

By Henrique Almeida

Angola is still a long way off from tempting U.S. banks into resuming dollar-clearing services despite making progress in combating money laundering, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

“American banks are unlikely to come back to Angola anytime soon,” Akin Majekodunmi, a London-based senior analyst at Moody’s, said in an interview on Wednesday. “This industry, if you like, doesn’t make much commercial sense for them anymore.”

Bank of America Corp. halted dollar supplies to Angolan lenders in 2015, five years after a Senate report showed how a convicted arms dealer moved millions of dollars into the U.S. Other banks followed, triggering an exodus of foreign workers who got paid in greenbacks and worsening an economic crisis that began soon after oil prices started to fall in 2014. Oil accounts for more than 90 percent of Angola’s exports.

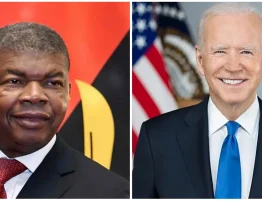

The new government of President Joao Lourenco, who took over last month after the 38-year rule of Jose Eduardo dos Santos, has signaled that reforms initiated by the previous administration to the banking sector will continue. Lourenco reappointed Finance Minister Archer Mangueira for another term and has retained, for now, Valter Filipe Duarte da Silva as governor of the central bank.

The advocacy group Financial Action Task Force removed Angola from its blacklist last year, citing significant progress in the fight against money laundering. Still, Transparency International has ranked Angola among the world’s 20 most corrupt nations for the past three years.

Viable Alternatives

A spokesman for Angola’s central bank didn’t return requests for comment by phone or email.

For large American banks, providing dollar clearing services to Angolan lenders may not generate enough profit to compensate for potential fines they may face at home for doing business with a bank not fully compliant with U.S. regulations, according to Majekodunmi.

Africa’s second-biggest oil producer relies on dollars and other foreign currencies to import almost all of its products following a 27-year war that ended in 2002. The local currency, the kwanza, isn’t traded abroad.

The euro has been a “viable alternative” for Angolan banks, which are also using the South African rand instead of dollars, said Majekodunmi. “Some European banks are also providing dollar clearing services but it takes longer, it’s more expensive and you can’t do big transactions.”

While Angola’s banking system still faces challenges because of limited access to dollars and a high level of non-performing loans, the country’s lenders still have a strong potential for growth, said Majekodunmi. Only 47 percent of Angolans used banking services in 2014, according to a report by KPMG LLP last year.

“There’s still a lot of capacity to grow their deposit base and use that money to re-lend to the private sector,” he said. “The issue with banks now is there is a lack of lending opportunities. Most of them really just put their funds back into government securities.”

— With assistance by Candido Mendes