By Shilda Cardoso|Friends of Angola

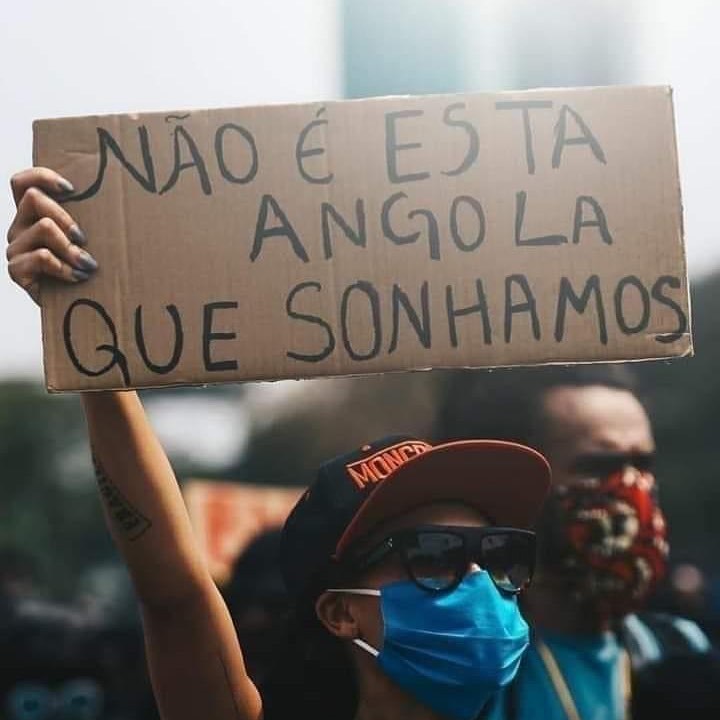

On the eve of the electoral campaigns for the August 24th elections, the limited attention to the topic of power transition from the interested parties in Angola is quite concerning. Given the country’s long history of civil conflict, numerous unfulfilled treaties, and highly contested elections by opposition parties, the lack of analysis about an eventual power transition is alarming. Whether the current regime is to maintain or not in power, the country should be engaged in democratic principles and seek to discuss how we guarantee a peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another as the ultimate expression of the rule of law.

The MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) has been in power since the country’s independence from Portugal in 1975. After the end of a 38-year rule in 2017 by the recently deceased President José Eduardo dos Santos, the party steered by João Lourenço since then is now seeking a second term. Naturally, the regime anticipates a win for its overall policy continuity and cement gains made under President João Lourenço’s political and economic reform agenda. In fact, it is understandable since one competes preferably to win, especially in politics. However, as evident from the previous four elections, the MPLA regime does not compete in elections in Angola; it participates and wins exclusively. It seldom discusses its agenda in the event of a loss. For a country harvesting and consolidating its democracy, this attitude is troublesome.

The incumbent regime and its members dare not mention an eventual defeat. They do not think about one, much less prepare for one. The question is whether we can consider that the country will hold free and fair elections when the ruling party is preparing for VICTORY in case it wins and VICTORY if it loses. In the regime’s book, the what happens if we lose chapter is entirely blank, or yet, possibly reserved for other editions. To worsen matters, the powers reserved for check and balances, namely the Constitutional Court and the National Electoral Commission, are equally silent on the subject. Why do we not have these institutions promoting the discussion on how a peaceful transfer of power will be guaranteed? The public needs clarity on who are the key nonpartisan players and institutions in the presidential and governmental transitions. Moroso, the public needs to understand how the regime intends to deal with an eventual loss. If the regime cannot respond to such public interest now, we cannot expect them to live that reality after the elections.

On the eve of the electoral campaigns for the August 24th elections, the limited attention to the topic of power transition from the interested parties in Angola is quite concerning. Given the country’s long history of civil conflict, numerous unfulfilled treaties, and highly contested elections by opposition parties, the lack of analysis about an eventual power transition is alarming. Whether the current regime is to maintain or not in power, the country should be engaged in democratic principles and seek to discuss how we guarantee a peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another as the ultimate expression of the rule of law.

The MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) has been in power since the country’s independence from Portugal in 1975. After the end of a 38-year rule in 2017 by the recently deceased President José Eduardo dos Santos, the party steered by João Lourenço since then is now seeking a second term. Naturally, the regime anticipates a win for its overall policy continuity and cement gains made under President João Lourenço’s political and economic reform agenda. In fact, it is understandable since one competes preferably to win, especially in politics. However, as evident from the previous four elections, the MPLA regime does not compete in elections in Angola; it participates and wins exclusively. It seldom discusses its agenda in the event of a loss. For a country harvesting and consolidating its democracy, this attitude is troublesome.

The incumbent regime and its members dare not mention an eventual defeat. They do not think about one, much less prepare for one. The question is whether we can consider that the country will hold free and fair elections when the ruling party is preparing for VICTORY in case it wins and VICTORY if it loses. In the regime’s book, the what happens if we lose chapter is entirely blank, or yet, possibly reserved for other editions. To worsen matters, the powers reserved for check and balances, namely the Constitutional Court and the National Electoral Commission, are equally silent on the subject. Why do we not have these institutions promoting the discussion on how a peaceful transfer of power will be guaranteed? The public needs clarity on who are the key nonpartisan players and institutions in the presidential and governmental transitions. Moroso, the public needs to understand how the regime intends to deal with an eventual loss. If the regime cannot respond to such public interest now, we cannot expect them to live that reality after the elections.

Let this be a critique of the opposition too. The opposition cannot rest comfortably, not knowing what its political adversary plans to do in the event of a loss. It is often the mistake of opposition parties in Africa to ignore this element before an election. However, after elections, it becomes clear that incumbent regimes that never prepare for a potential loss use anything in their reach to maintain power. Like in a boxing match, would one get in a ring with a fighter who does not believe in defeat or does not know how he would react to one? That would be a dangerous encounter because the opponent would likely use illegal strikes to win. Thus, let us normalize this conversation among all political parties running in the elections. As we approach the political campaigns, let the matter be discussed at every opportunity, particularly to inform the public about the peaceful transfer of power. Let the public be assured that regardless of the electoral outcomes, all interested parties, particularly the incumbent party, are prepared to respect the rule of law of an eventual loss and facilitate a transition of power.