By Mary Harper

Africa editor, BBC World Service News

There has been a lot of talk about how not much is going to change in Angola, despite the impending departure of President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has served for nearly 40 years.

The oil-rich country, often described as one of the most corrupt in the world, has only had two leaders since independence from Portugal in 1975.

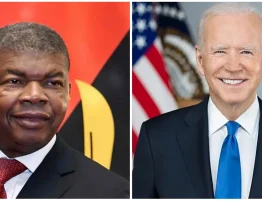

Provisional results from Angola’s recent election put the governing MPLA party in an unassailable lead, which means the former defence minister, Joao Laurenco, is going to be the next president.

But at least one thing will be different.

Who is Angola’s JLo?

The new head of state will not be able to govern in the same way as his predecessor.

The outgoing President dos Santos is still the head of the MPLA which has governed Angola since independence, transforming it from a hardline communist party to a freewheeling capitalist one.

Joao Laurenco is set to become the country’s next president

This often invisible, but phenomenally cunning politician – popularly known as Zedu – is not going to retire gracefully, despite consistent reports of ill health.

He will remain powerful, and he will remain in the shadows.

Before the election, a law was passed preventing the new president from firing the heads of the army, police and intelligence services for eight years.

Plus, for now at least, the dos Santos family tentacles will keep a firm grip on the economy.

The president’s daughter, Isabel – Africa’s richest woman – runs the state oil company.

One his sons, Jose, is in charge of the $5bn (£3.9bn) state-owned investment fund.

Angolans choose new leader to replace Jose Eduardo dos Santos

Angola’s election explained

Jose Dos Santos: Angolan wealth fund chief and president’s son

Angola timeline

Unravelling Angola’s wealth from a tiny elite of super-rich families will be a mammoth task – and there may well be a lack of will to do so.

Despite predictions of social unrest – even an Angolan Spring – a few families continue to become richer and treat the country as their playground.

A measly tuna fish sandwich on the glamorous beach front near the capital Luanda will set you back $40.

Porsche cars, purchased from a local showroom, purr by, their occupants dripping with designer wear.

Super-yachts crowd the ocean and high-rise buildings with multi-million dollar apartments line the horizon.

Angola’s oil wealth has seen areas of its capital, Luanda, transformed into a playground for the rich

It is hard to believe that just 15 years ago, Angola was still being ripped apart by a civil war which lasted 27 years, and which had been preceded by a long, bitter struggle for independence.

For all the criticism of President Dos Santos, he is the man who ended the war following the killing in 2002 of the Unita rebel leader Jonas Savimbi.

Unlike many other countries, Angola has not slipped back into conflict.

It is repressive, corrupt and intolerant of dissent, but war has not returned.

Growth for some Not long after the conflict ended, the country became a miracle, at least economically.

For some years, it was the world’s fastest growing economy.

Chinese and other foreigners rushed in to build roads, railways and new cities.

Even citizens of the former colonial power, Portugal, fled economic collapse at home for lucrative jobs in Angola.

But most of the grand infrastructure projects did not improve the lives of Angola’s poorest, 70% of whom live on less than $2 ($1.50) a day.

Hawkers sell their products in an improvised market across a train track in the Viana district in LuandaImage

The vast majority of Angolans live on little money.

The United Nations says 20% of Angola’s children die before their fifth birthday – one of the highest child mortality rates on earth.

During the long years of war, the poverty, the lack of schools and hospitals could be excused. But no longer.

Now that oil prices have crashed, inflation has rocketed to 40% and annual economic growth has plummeted.

Politicians must be regretting that they failed to honour promises of economic diversification.

Angola is blessed with gold, diamonds, fertile land, a long seaboard and, for such a huge landmass, a relatively small population.

For decades, Angola’s crafty, invisible president worked hard to keep the poor invisible too.

He bulldozed their slum settlements to make way for glitzy shopping malls and housing developments, locking up many who complained.

But keeping a lid on the more than two-thirds of Angolans who are under 25 – and who are social media savvy, and out of work and education – will be a mighty challenge for the new man at the top.

For a country so abundant with natural resources, perhaps it is time to stop treating it like a family business.